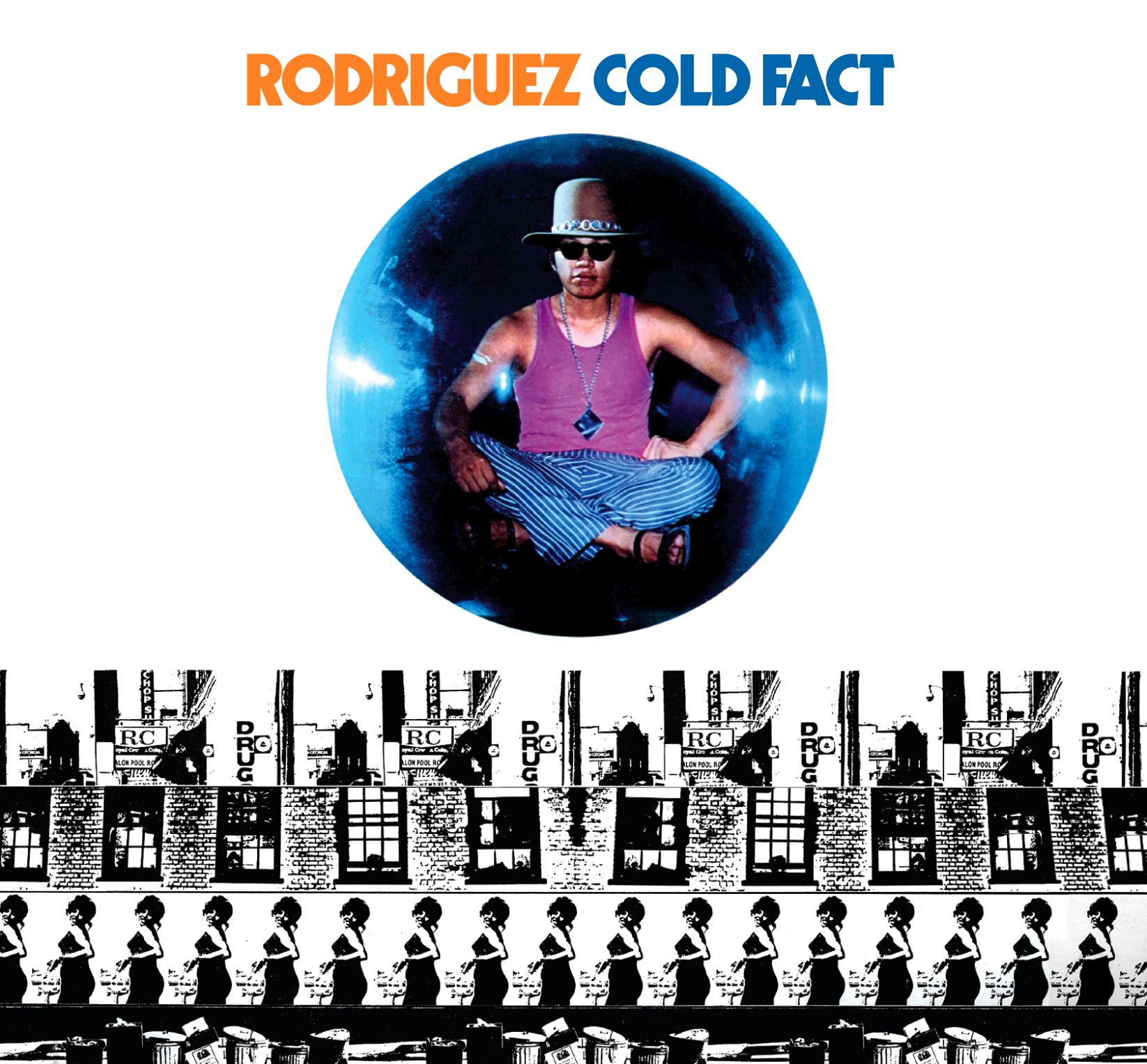

The voice of Rodriguez is instantly classic; some peculiar timbre of his resonant tenor sounds perfectly timeless, like Neil Young or Bob Dylan with an added unpretentious grit gleaned from hanging on the hard streets of 1960’s Detroit. Born as Sixto Rodriguez into a poor Mexican-American family in 1942, Rodriguez spins stories of drugs, hardship, and resentment against the establishment into his 1970 debut record Cold Fact with hard-gained authenticity. It’s an absolute masterpiece of a folk-rock album, and it should have swept the nation, electrified the anti-establishment movement, and sold like hot cakes; except it didn’t.

Cold Fact, for all its anti-establishment anthems, compelling lyrics, and imaginative instrumentation, sold poorly. His 1971 follow-up Coming from Reality did not do any better. Rodriguez quit his dreams of a music career, got a philosophy degree, and worked as a construction worker in Detroit for the rest of his life. Or, almost the rest of his life; but we’ll come back to that.

Cold Fact, the transcendent album with all the talent and class consciousness to rouse an entire country to frenzy, was not dead but dormant; while Rodriguez had given up on his career – and indeed, Cold Fact was a dud in America – his album began to slowly receive radio play in Australia. The trickle became a stream, and Rodriguez managed to squeeze out a few Australian tours in the late 70’s and early 80’s. But by 1981 the Australian gig was up, and Rodriguez returned to his simple, hardworking life in America.

Completely unbeknownst to Rodriguez, however, the stream in Australia was a veritable waterfall in South Africa. Cold Fact – unbelievably, beautifully – had become the clarion call for the burgeoning anti-apartheid movement. The lyrics alluding to sex, drugs, and the cruelty of the establishment struck a chord with South Africans fed up with an oppressive, ultra-conservative government seemingly hell-bent on destroying its own citizens. In South Africa, Cold Fact was “more famous than Abbey Road”. South Africans had tattoos of the Cold Fact cover. As quoted by The Guardian, a South African soldier summed up the sentiment of the time, saying: “We made love to your music, we made war to your music”.

Rodriguez’ incredible fame in South Africa soon led to his canonization as a mythological figure. No one knew who Rodriguez was or where he lived. The near-unanimous sentiment among South Africans at the time was that, whoever Rodriguez might have been, he was most certainly dead. Legends of his demise speculated, swirled, and gained momentum. Stories reverently spoke of how he shot himself on stage, or perhaps he immolated himself on stage? Overdosed on heroin, even? No one could agree on just how he died, but the legends of his death turned him into a sort of anti-apartheid martyr, a folk hero whose dramatic death further cemented his legacy as a resistance icon.

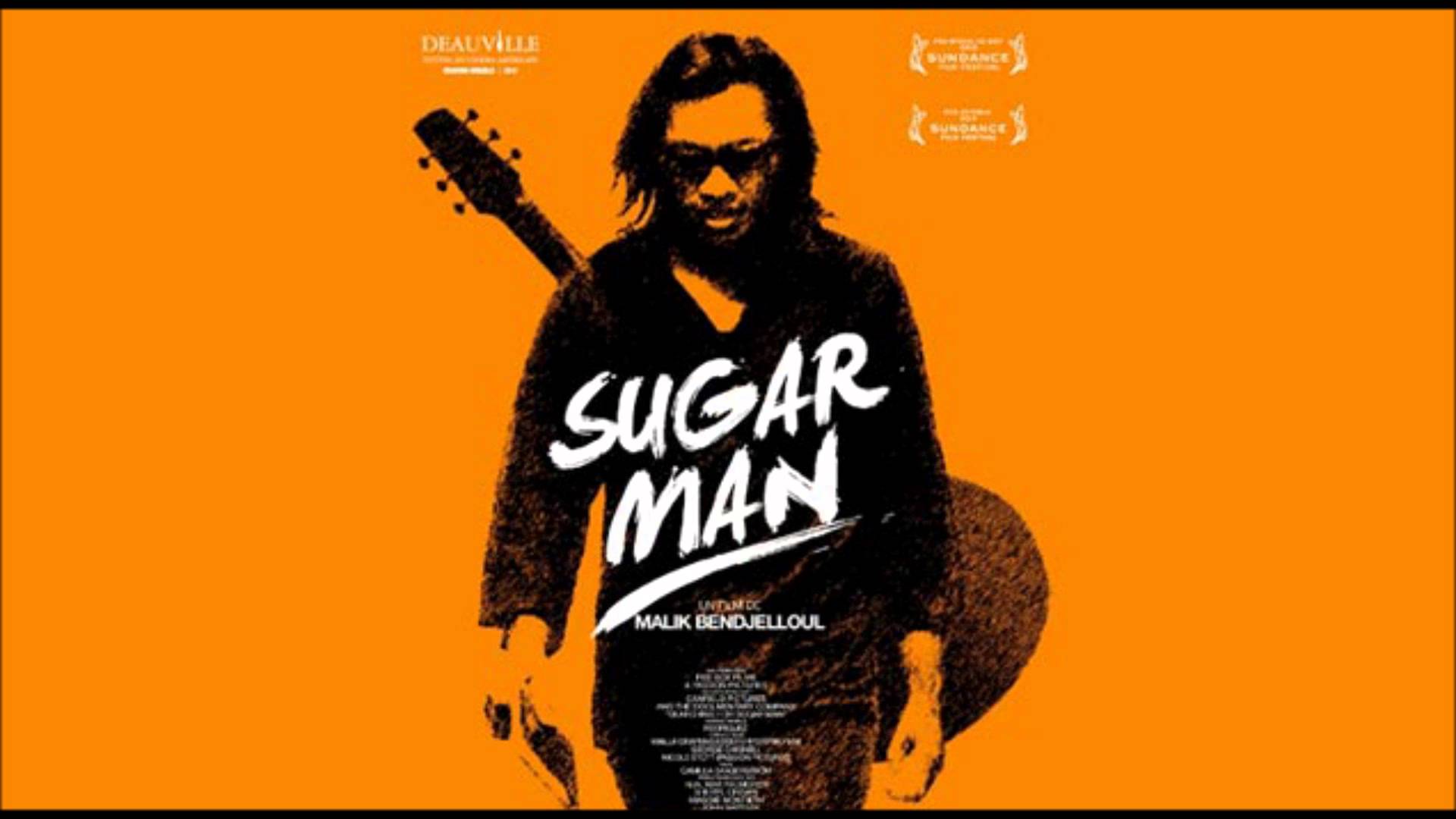

Rodriguez remained utterly unaware of his South African popularity until 1998 when his daughter found a fan website dedicated to him. Through the hard work of a few South African superfans who tracked him down, Rodriguez was finally convinced that his success was not a cruel prank, and he agreed to tour South Africa. The tour was wildly successful, and today Rodriguez tours the world, playing Cold Fact and Coming to Reality to sold-out venues, forty years late. (If you’d like to know more details about the amazing story of Sixto Rodriguez, I highly recommend watching Searching for Sugar Man, the Oscar-award winning 2012 documentary about those same South African fans who tracked Rodriguez down in 1998.)

So that’s the story of Rodriguez. But the music of Cold Fact deserves at least as many words. Cold Fact is often misidentified as psychedelic rock, but this is a misnomer; with the exception of “Sugar Man”, and a few psychedelic flourishes here and there, this is not a psych rock album. Cold Fact is, however, a folk-rock album somehow both lush and sparse at once. The instrumentation features trumpets and oboes and violins and marimba and much more, but most of the album is hardly more than an acoustic guitar and the effortlessly emotive voice of Rodriguez.

The psychedelic elements present on Cold Fact are mostly confined to the first two songs. “Sugar Man” is a uniquely plaintive track that uses the whirls, trills, and swoops of electronic instruments to mimic the sensory experience of a drug-induced psychedelic state. Rodriguez punctuates this feeling as the song fades out; the production causes his voice to echo back and forth, and he seems to slowly fade off into the distance as he laments: “Sugarman / you’re the answer / that makes my questions disappear…”

“Only Good for Conversation” approaches psych rock from a different angle, opting for ultra-fuzzy guitars to beef through a catchy riff on one of the angriest songs on the record. “Crucify Your Mind” represents the end of the major psychedelic influences on the record, and introduces Rodriguez’ greatest strength. Rodriguez has an amazing talent to wring melody out of notes so understated they nearly sound conversational. The dynamic range between notes is normally quite small, but the conviction of Rodriguez’ phrasing and the honest beauty of his lyrics caresses sweetness out of words where lesser singers would bludgeon them.

These masterful ballads are Rodriguez’ zenith, and fortunately, Cold Fact is chock full of them. “Hate Street Dialogue”, “Forget It”, “Like Janis”, and “Jane S. Piddy” all have that same understated, lightning-in-a-bottle magic. The slow pace and simple poetry of the ballads make listeners consider their quiet prosody and surprising depth. Consider Rodriguez’ lost hope on a broken love: “If there was a word but magic’s absurd / I’d make one dream come true / It didn’t work out but don’t ever doubt / How I felt about you.”

The straightforward truth of Rodriguez’ lyrics no doubt aided his surge to success in South Africa. “This is Not a Song, It’s an Outburst: Or, The Establishment Blues” is as blunt as could be about the state of affairs: “The mayor hides the crime rate / Councilwoman hesitates / Public gets irate / But forget the vote date / Weatherman complaining, predicted sun, it’s raining / Everyone’s protesting, boyfriend keeps suggesting / You’re not like all of the rest”. The lyrics are probably about Detroit specifically, but it’s easy to see how South Africans projected the lyrics onto their contemporary issues. “Hate Street Dialogue” and “Rich Folks Hoax” are similarly critical of the establishment. “Rich Folks Hoax” in particular shows off Rodriguez’ poetic chops: “The priest is preaching / From a shallow grave / He counts his money / Then he paints you saved.”

The album concludes with “Jane S. Piddy”, perhaps Rodriguez’ best song. It’s a beautiful rambling ballad in the mold of Bob Dylan’s simple epics, drifting in a sea of disaffection but not quite hopeless. The chord progressions never change, but it’s not a boring song; instead, the repeated melody becomes a hypnotic canvas. On this track, Rodriguez’ voice is distorted with a slight echo, creating the odd feeling that his voice is coming from every direction at once. Under this vocal distortion, the lyrics seem to take on an almost prophetic quality. They aren’t sung so much as they seem to be delivered from on high, enveloping you, narrating your own loneliness and confusion to you. It’s a rather spectacular and thought-provoking effect and concludes the album powerfully.

One of the fascinating things about Cold Fact is that one has to wonder how many other Rodriguez’ are out there, undiscovered and unappreciated, having long lost hope for their time in the sun. Rodriguez’ heyday may have come thirty years late, but it seems some seeds are destined to grow, no matter how long they may lay dormant. Rodriguez’ style is wholly inimitable and must be heard by anyone who enjoys 70’s folk rock.

“Thanks for your time, and you can thank me for mine. And after that’s said, forget it. Bag it, man.” – Rodriguez, “Jane S. Piddy”.