Punk rock, in its truest sense, was founded on rebellion through self-expression: wild self-expression, filled with passion that meant displaying yourself to the world how you are, no matter how odd, fearing not whatever repercussions came your way. It led to a generation of freaks, kids using everything from bullet belts to safety pins as some sort of bizarre fashion statement that helped to display their anti-conformity agenda. It was meant for the individual and refused to be tamed.

That was, of course, until it was. What was once a way to put individuality and rebellion on show soon became a bit too much of a fashion show, a counter culture with its own sense of conformity. Splinter groups of the style soon formed, each with their own interpretation of exactly what it meant to be punk, and each with their own strict code of ethics that helped to define that. Soon it seemed as if there was individuality left. As if the very conformity punk had been established to rebel against had subverted the counter culture, tacitly placing a choke hold on it which it could not break.

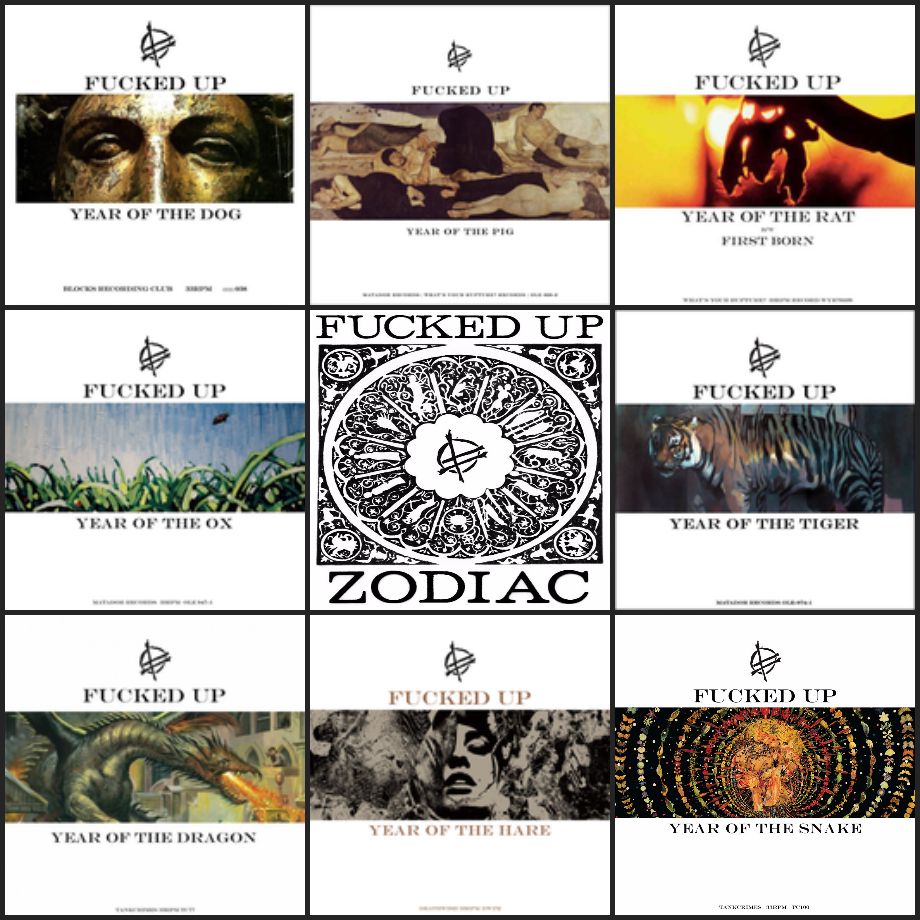

This trend continued for a long time, and continues still even today. However, there are some punk bands that still manage to subvert the grand cliches, both musical and stylistic, that overtook punk. One of those bands is Canadian hardcore/punk/experimental heroes Fucked Up, a band who has never shied away from pushing punk to its very furthest limits, effectively achieving the goals punk initially set out to accomplish. Recently I was lucky enough to talk to their drummer Jonah Falco about exactly what inspires Fucked Up to constantly push the boundaries of punk music, as well as their most recent release, Year of the Snake.

What was the initial inspiration behind the zodiac animal releases? To me they seem very oddly conceptual and theatric, especially in the context of a lot of other punk and hardcore music.

Jonah Falco: Like so many things we’ve done it ends up being slightly coincidental. We were recording in a studio in Toronto, and we sort of set this challenge to ourself to write this long, plotting song that was supposed to sound like “I Wanna Be Your Dog” by The Stooges. Just as a kind of cynical one-ups-manship towards some radio DJ that we were sort of collectively mocking.

So we recorded this song and were having a lot of fun with it, adding dumb stuff, making noise, sort of getting our feet wet with making these really long, unconventional Fucked Up songs and then it so happened that it was the night of the Super Bowl, and the Rolling Stones were playing the half time show. And so we got the engineer to record the Rolling Stones’ banter before they went on and had them put it in the song. It was like this weird thing where all these elements were aligning and it also happened to be Chinese New Year or like the calendar day in which the Year of the Dog was starting, so we thought we would call the song “Year of the Dog”.

And then, from then, we just set ourselves the challenge of doing one ever year to coincide with the zodiac. So it was like a happy accident, really. And then the more we did it, the more it became a very intentional and specific space to make these musical gestures we weren’t really making in other places.

This kind of goes off that a bit, but to me the Zodiac series thing is a very theatrical thing, especially in the context of punk and hardcore because a lot of time I see a lot of bands, and even a lot of my own friends, in these scenes talk about how there shouldn’t be that level of “flair” or performance in it. Do you ever get that backlash or acknowledge that all when you all write or is it something you choose to ignore?

Jonah: I think we’ve been ignoring that the entire time and it’s not really… I’m sure there is backlash but the whole point of us making those gestures is not to sort of create a smooth transition of like musical power between the things that are readily accepted and the things that we do. I think that we especially, we put a lot of pretense into the music and a lot of pretense into the lyrics. There’s so much of a screen or a filter between the immediacy of traditional hardcore punk and what we do. We’re using the format to get somewhere else in a way, and specifically with the zodiac people may or may not have issues with the way Fucked Up is approaching the hardcore punk medium, and for us that just sort of comes natural to do what we want. And then, with the zodiac in particular, it’s a place for us to do really what we would never otherwise do. In particular it’s not a hardcore gesture, it’s the time we get to experiment the most freely and I think that is kind of an internal genre for the zodiac series for Fucked Up it has a lot in common…the lengths, the approaches to the music, not really matching anything we’ve done or fitting into hardcore.

But I also think not having received backlash does not mean most people accept it; I think it means most people have flipped their off-switch when it comes to the 25 minute psychedelic. jams. But [it’s] their loss, isn’t it?

I wanted to talk about this too because I’ve been into punk and hardcore since I was about 12 now, and I’ve just noticed there are so many straight edge bands, there are a lot of ones that love talking about getting really drunk, and then there are a lot of jokingly stoner bands, but to me it’s really interesting because I hear Fucked Up and it’s…weed and psychedelics. I feel like it’s not touched on a lot in punk.

Jonah: I mean, yeah it’s not on purpose, it’s not really like we’re making a statement or add that characteristic to our band, at all. Fucked Up is simultaneously filled with content and completely baseless, and I think you can chalk it up to that.

Jonah Falco of Fucked Up. (Photo: Bruce Emberley/Aesthetic Magazine Toronto)

And I’m sorry because that sounded like a really stupid question, but it actually goes into my next question. In the press release I got for “Year of the Snake”, what I thought I was really interesting is that it said “‘Year of the Snake’ documents the journey of self care and opening awareness through the use of psychedelics and medicinal plants”. I don’t know how much of that you all influenced in the press release but I was wondering how it related to the release, if at all.

Jonah: The song is clearly about that, it’s about a journey and the music itself is reflective of the kind of things you can experience on psychedelics…Damian [Abraham, vocals] is so embedded and emboldened in medicinal marijuana, weed activism, things like that. I think there’s a huge amount of benefit to, especially the thought process of committing that to paper and to tape so to speak. And, yeah, so it is completely reflective of that, but I’m not sure necessarily it’s the sole characteristic.

But the music is really representative of something like that. Trying to find continuity, or safety, or calm is something that is disorienting or not entirely your reality, and in the context of a Fucked Up song it’s like the gesture of the music being completely different is one way of being uncomfortable or outside of yourself. But all of a sudden you find yourself at least hearing a repetitive riff, a verse and chorus, and then, as the song kind of arcs towards the conventional climax, all the sudden, where you think you get to wake up, or feel sober, or feel normal again, you get pushed into another section which is completely disorienting, or different, something you didn’t expect or maybe didn’t want to see. It’s like you don’t get to just finish with it, it has [to] leave your system—you don’t just get to walk away. So I think the music does sort of represent like a, you know, trip in a kind of certain way.

And I kind of wanted to ask about that too because I’ve never been into the zodiac signs, or any of that kind of stuff, so I had to do a little bit of research to kind of try and understand what the zodiac signs actually meant. I found out that the zodiac snake personality types tend to be calm, wise, and searching for broader answers. So when you were writing this song did you do that with the snake characteristics in mind and how that might connect to the psychedelic exploration and everything?

Jonah: I have a feeling that the parallels are conveniently there and usually when we write these songs we try and incorporate from a writerly perspective, the elements, like the natural elements, and the attributes of the sign we are trying to talk about. It’s not really enough to just sort of name your song “Year Of The Snake” and then it’s just called “Year Of The Snake” and it comes out vaguely in the year of the snake. Everything is supposed to be referential and representative in that.

Finding the pathway for calm, wisdom, and self searching conveniently came at the right time for Fucked Up, as a band, to write this song as well. We’re in between records, touring a little less, that kind of thing. It was a perfect time for reflection. Maybe the stars just aligned for us—who can say.

So if self reflection is the theme of “Year Of The Snake,” what do the past zodiac releases kind of deal with? I tried to Google it, and it’s a bit hard to find.

Jonah: [Laughs] Yeah, I mean, all the past zodiac releases have just, uh, kind of, they’re pieces of writing. All of Fucked Up’s records focus on the development of an idea, in terms of what the songs are about. You know, like, Hidden World, for instance, had a sort of common theme of the beginning of the planet…actually that was more Chemistry of Common Life, but anyways, all the records, and here’s me, the drummer, trying to talk to you about the lyrics right? But every Fucked Up record seeks to encompass a single idea and develop that through the record. Whether it’s about philosophy, whether it’s about the planet, whether it’s about evolution, whether it’s about the repetitive and punishing nature of contemporary living, whatever you want.

And so these records are no different, we find a topic and you write a missive that speaks to those things. The other zodiac records had metaphorical pulls like Year Of The Pig was coinciding with the brutal murder by this man named Robert Piktman of sex workers on the West Coast, and Year Of The Ox had clear metaphors for things about being indebted and obliged to work and having a work animal that has been beaten down and has to find its way to a sort of freedom. Year Of The Hare had shades of speaking about mental health, repetition, and maybe going crazy, things like that. So all of these are specific to the animal with attributes of sort of what the zodiac calendar can tell us about the year of the hare, people born in the year of the hare and so on and so on.

So that’s pretty much all I have to cover with the zodiac stuff, and thank you answering all those questions because those records honestly interest the shit out of me but I’ve been kind of a bit lost on the meanings.

Jonah: Yeah if you just read the lyrics, and then just think about what was happening that year, you know? They’re sort of a reflection on the quote unquote temperature of the year, and it’s just like…what do writers write about? Just like what they experience and what they’re thinking.

This one is specifically for you as the drummer, because it honestly confused the shit out of me when I initially bought the Glass Boys vinyl and got a second copy with entirely half time drumming. I thought it was the weirdest, coolest thing and still stands out as really bizarre, so what was the inspiration with that?

Jonah: Um, we were just writing, we were writing Glass Boys and we kinda had this idea for an intro for..uh…uhhh…what’s the first song on Glass Boys? We have all these alternate names for all our songs, our name for the first song on Glass Boys is “Chop Beat”…anyway, because it had this sort of interesting rhythmic pattern, and it had this sort of Zeppelin-y half time thing and we just thought “Well wouldn’t it be cool if that went all the way through?” and I must have said, “Oh no, it’ll be too boring” and we just compromised and said “well, let’s do both.” And it occurred to us all the things that we’re writing are straight-forward, all the tempos are straight-forward and have a very easily attainable half way point, a good fifty percent. And most of them were able to be transformed into these other songs and we actually have, as you know, both drum beats going at the same time and, in a way, after the fact, it ends up alluding to a former self or a future self.

It’s like the fast drums are the younger Fucked Up and the slow drums are maybe a slightly more efficient, undercapable, older versions of ourselves that have to sort of slow down and be reflective. Or when you’re forced to reflect and forced to remember. It’s like an old person saying “I can still play like I used to” but then finding out you can only do it half as fast. But rhythmically I think it makes it really interesting, and considering some of the poppy songs on that record, I think it lends them a bit more depth to have a complicated element.

And as always with Fucked Up we tend to, on purpose, try and go about things “the wrong way” in the interest of getting an interesting result. Most people would try and write a polyrhythm and write it out exactly, where as we just wrote an entire song and said “Ok now, play it at half the tempo at the same time”. You can imagine the look on the face of the engineer, the guy I recorded the drums with, John probably….I’m sure he wanted to throw me in front of a jumbo jet at the end of it.”

That actually kind of goes into my question as well too, when you’re talking about how kind of at a certain point you need to be reflective and I guess slow down a bit. I’ve noticed that the experimentation has increased, like the collaboration with the throat singer Tanya Tacaq, and I was wondering if that’s at all reflective of where the band is headed. I remember reading about how you played in an MTV bathroom, and destroyed it. Do you think you’re getting closer to that point now—

Jonah: [Laughs] The Point where we no longer wanna destroy bathrooms?

—where you might be slowing down a bit and getting more reflective?

Jonah: Well, I just think that the longer the band goes on the more you have to be considerate of what you mean to yourself and what you mean to the people who are listening. And I think that’s the most difficult balance for a band as old as we are, and for lack of a better word, a band as specific as we are. You have to please yourself, but I think, and Fucked Up is already incredibly indulgent, and thing like the Tanya record are part of the indulgence. Like the side of pure contemplation and wonder on our part, and again that was something that sort of had to be made and thought of in the same instance. So it’s not like representative of a new direction of Fucked Up but it is representative of how we would like to think about music. And, if you’ve been playing music for fifteen years, and maybe you haven’t quite thought about what it means to be making music, or not exactly what music is, but when or where music is, or how music is, these are things we just wanna know as we get on in years. Fortunately, people who have been listening to Fucked Up for a long time, part of that answer is still in playing really loud, fast music. There’s hope for us all, to be considered here. But I think those types of experiments are necessary, and we’re very lucky to have a platform in which to explore these things publicly, and that our whimsy turns out sounding kind of interesting. At least interesting enough to talk about. So I don’t know. It’s a bit of a summary, I know, more than a direct answer, but uh, yeah.

That’s all good. We end every interview with the blog with one question, a bit of a stupid question, but uh, how do you like your eggs?

Jonah: [Laughs] Oh? Hmm. I like em’ over easy.