Welcome to “Beyond the Veil“! In this feature, its name (partially) taken from the Gods of Eden track, we’re going to delve into some theoretical aspect of the music we love in an effort to elucidate the behind-the-scenes workings at play, but in a largely jargon-free manner intended to be accessible to those who don’t necessarily have a music theory background.

Metal’s propensity for non-standard scales is no secret, yet as scales themselves go, today’s topic of choice might be something that could be considered a little more closely-guarded. However, the uniquely atonal nature of whole-tone scales makes them very easily recognizable once one knows what to look for, and easily makes them one of the more intriguing tricks in musicians’ playbooks.

But let’s back up for a quick second and explain some key terms before moving forward. A scale is an ordered group of notes that, when used together, often evoke a certain sound or feeling. Scales can be defined by their intervals, which is a term for the distances between notes. We’ve covered a couple of these in the past, so this shouldn’t be news to readers of past Beyond the Veil instalments, but an explanation of whole-tone scales in particular necessitates some more definitions past just that.

Namely, we’re going to go one step (heh) further and actually define two of these aforementioned intervals — the half step and the whole step. These aren’t too difficult to understand: a half step is essentially the distance between two adjacent notes, which can also be described as a semitone apart. For instance, C and C# would be considered notes a semitone apart. On the other hand, a whole step describes notes that are two semitones (collectively described as a whole tone) apart, such as C and D (since there’s a C# in between).

For the most part, scales generally consist of notes that are mixed combinations of half steps and whole steps apart from each other, with these combinations picked out to emphasize certain consonant intervals over others. This is where the whole-tone scale differs: rather than being a mix of these two intervals, it consists exclusively of notes that are whole tones apart from each other, as the name implies.

This actually sounds a little strange to our ears, since most scales we’re used to hearing tend to be arranged such that they have a consistent feeling (often major or minor) all the way through. However, as a consequence of its constituents being whole tones apart from each other, the whole-tone scale includes everything from the nice and harmonious major third, which forms the core building block of any major chord, to the horribly dissonant tritone, which we’ve talked about at length before.

So what does having such a disparate mix of intervals sound like when used together? Well… dreamy, surprisingly enough. ‘Dreamy’, ‘mysterious’, and ‘alien-like’ are often terms used to describe whole-tone scales, as they sound just off enough to our ears to still make some semblance of sense while still being all over the place.

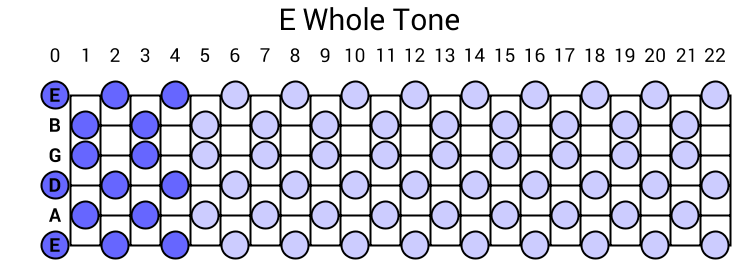

Before we draw this long-winded introduction to a close, one particular advantage of whole-tone scales from a guitarist’s perspective is worth mentioning. Much like the diminished scale, used blazingly fast in tech death and the like, the whole tone scale as visualized on a guitar fretboard is incredibly symmetrical and straightforward, due to the consistent spacing between notes. This makes it very easy to shred through for a lead guitarist, since the guitarist’s fretting hand can just repeat the same shape over and over in moving through the scale.

via jguitar.com

We kick off today’s examples with instrumental prog innovators Animals as Leaders, who at this point need little introduction for most metal fans. The twin guitar work of Tosin Abasi and Javier Reyes is often complex beyond compare, with both drawing from a wide array of influences in writing their technical compositions.

On “Cylindrical Sea” from sophomore album Weightless, Abasi and co. venture into territory that’s a little out of the ordinary by the band’s own standards, in putting together lead parts so well-crafted that this isn’t even the first time I’m writing about them.

The second solo in “Cylindrical Sea” (2:30) begins with a whole-tone phrase, after which Abasi keeps flitting in and out of using whole-tone sounds in order to lend an otherworldly feeling to his leads. I realize it can be a little hard to follow, considering the speed at which he generally plays, but I find “Cylindrical Sea” to be a good example of leads tastefully augmented with whole-tone sounds rather than being based entirely off them.

After starting off with one of the faster examples out there, perhaps it might be pertinent to kick things back a notch. Admittedly, Ron Jarzombek’s instrumental tech death outfit Blotted Science isn’t exactly known for keeping things all too simple or straightforward, yet “Activation Synthesis Theory” off of debut The Machinations of Dementia actually contains some midtempo riffs that make for some great and easy-to-understand examples of whole-tone usage.

At 2:44, a chaotic verse section gives way to an almost dreamy-sounding line that consists entirely of — you guessed it — notes conforming entirely to the whole-tone scale. Interestingly enough, in Jarzombek’s case, his usage of the scale has more to do with his affinity for the twelve-tone technique, since it allows him to organize his ‘tone rows’ neatly. Underneath the lead line, the low-end rhythm stays within the realm of the scale as well, before both guitars undergo a bit of a change up come 3:20.

We round out today’s article with Archspire, whose incredibly fresh take on tech death has quickly made them rising stars within the community. Sophomore album The Lucid Collective was widely hailed as one of the best modern tech death albums upon its release (and a ridiculously huge step up from its predecessor, no less), and amongst its many instant classics can be found live staple “Seven Crowns and the Oblivion Chain”:

“Seven Crowns” is a little different from our other examples, in that the whole-tone scale actually makes up the backbone of the song right off the bat rather than briefly showing up somewhere in between. The whole-tone nature of the riffs becomes particularly apparent from 0:17 onwards, as guitarists Dean Lamb and Tobi Morelli alternate between tremolo picking and swift harmonized runs.

Further listening:

Opeth – Nepenthe

Protest the Hero – Hair-Trigger

Gorod – Inner Alchemy