Welcome to “Beyond the Veil“! In this feature, its name (partially) taken from the Gods of Eden track, we’re going to delve into some theoretical aspect of the music we love in an effort to elucidate the behind-the-scenes workings at play, but in a largely jargon-free manner intended to be accessible to those who don’t necessarily have a music theory background.

For all the bad rap bass playing gets in rock music, bassists seem to get a lot more recognition and appreciation in metal circles. This is not something that’s uncalled for: playing bass in metal, particularly more technical metal, can be just as challenging as guitar playing, if not even more so in some circumstances. Plus, the fact that low-end riffage is pretty common and bass-intensive in the genre is only that much more conducive to bass work playing a bigger role, and the occasional influences from jazz and even funk only further that.

An interesting dimension to bass playing—and one that is borrowed largely from jazz fusion, to be clear—is the usage of fretless bass.

So, what is so special about fretless bass? To understand that, we need to understand what frets do. We’ve spoken a bit about what notes can do before. Most western music is based on a system that uses 12 notes. Frets are the tool on the guitar that help separate the range of sounds possible on the guitar into those 12 notes. When you remove them, you have all sounds possible in your hands. It’s kind of like climbing a hill instead of climbing stairs. You can step anywhere! But it’s also a lot more difficult to control, as you need to know exactly where to place your finger to get the sound you want. Of course, as per the linked editorial, sometimes you want to be deliberately off-note, which is the whole point of fretless bass. And since most fretless bass players play along with guitarists who use fretted guitars, it puts an extra burden on the bassist to know when to play along with the guitars and when to go into fretless ranges to create unique sounds.

Fretless bass also has a unique “bwoww” type of sound that is softer than regular bass, because the sound of a string is dependent on how it resonates when you hit it, and the metal frets on guitars give that a certain type of resonance, whereas a lack of frets changes the quality of that sound. Also, many fretless bassists emphasize this sound further by deliberately sliding between notes that are “frettable” notes versus “fretless exclusive” sounds, creating the unique sound that many associate with the instrument. When every sound in the spectrum is possible, there are many that just flat out don’t work well, so fretless bassists tend to stick to notes that are normally available to fretted players, and they use their excursions outside those notes to create a contrast. Some players take influences from Eastern/Middle Eastern music that use more than 12 notes and use scales available to those players.

While it might seem otherwise, frets are actually a newer addition to instruments, as classical instruments like the violin don’t have frets and are essentially fretless. However, since classical music generally emphasizes being in-key heavily, they don’t traditionally utilize the odd sounds that fretless bassists in metal tend to use. Jaco Pastorius, who played bass for the influential jazz band Weather Report, was one of the first players to use fretless bass. He used the smooth, sliding noises of fretless bass to add more character to the band’s sound (for example in “Birdland“). Following him, many jazz players started utilizing the instrument, and with early tech death being heavily jazz-influenced, several key players brought the same sound into metal, and the way they and Jaco played the instrument still defines its usage to date.

Another noteworthy aspect of fretless bass, especially in tech death, is production. Normally bass doesn’t stand out, it makes the rhythm section sound thicker, but with tech death bands, they often emphasize the bass in their sound so that the unique aspects of the instrument stand out. In all of these examples, you’ll notice how prominent the bass is.

Sean Malone of Cynic is probably the most directly obvious segue from the discussion about jazz into metal. He was originally a latin jazz player and the studio engineer where the genre-defining classic Focus was being recorded. When the band’s bassist quit shortly before the recording process started, he was drafted into playing bass for them, and the rest is history. His work on the album is full of delicious fretless noodling, but the most prominent example is probably the bass solo in “Textures”:

Two minutes and 24 seconds in, the bass solo has the sweet, smooth sound that is characteristic of fretless bass. He uses subtle slides and vibrato (“shaking” the note to change its pitch slightly) to make notes flow into each other, and he uses pitches that are slightly outside the 12-note system to give it that little “out there” vibe. This is a great example of using the fretless for its creamy sound in a jazzy context. The rest of the album has a lot of fretless moments as well, for example the clean breaks in “Veil of Maya“, but the latin jazz heritage is traceable directly in Textures.

The other originator of fretless bass in metal is Steve DiGiorgio, and he used it both in a jazzy context and also as a way of amplifying regular rhythm playing with “outside” note to add more character to the sound and make it sound weirder. His work with Death has come to influence many to pick up the instrument, and he has continued to use fretless guitar in many projects like Sadus, Testament, Vintersorg, Ephel Duath, Soen and Quo Vadis (more on that later). He could easily be cited as the most influential fretless bass player in metal, as his work is both prolific and prominent. “The Philosopher” by Death has several examples of it:

The riff at 1:46 is a great example. The guitars are playing regular power chords, and Steve is sliding between the notes the guitars are using to get the “bwoww” sound mentioned above. This takes what would be a simple riff to the next level by adding character to it that guitars simply couldn’t have done. The contrast between the rigid notes the guitar are playing and the smooth irreverence of the bass is what has come to be a characteristic of many tech death bands. Then, at 3:05 we have a fretless bass solo by him shortly before the guitar solo. Again we have the guitars playing power chords, and the bass is sliding between the notes emphasized by the guitars and out of them, creating a tonal contrast. This is the most important aspect of fretless playing. Being constantly off-note would sound overly weird and dissonant, but just hinting at some structure and then defying it creates a much more powerful effect, as breaking rules isn’t meaningful without having rules to begin with.

And now we’re at the pinnacle of modern tech death fretless bass playing. Dominic “Forest” Lapointe has made his mark on Canadian tech death bands Augury and Beyond Creation, and his playing goes above and beyond in terms of ridiculous fretless bass usage. Beyond Creation’s “Omnipresent Perception” is perhaps the defining example of his work, even though both albums by the band have insane fretless playing. The lead single from the band’s 2011 debut The Aura is definitely the stand-out though, with melodic 8-string guitar work being amplified by his masterful playing:

Where to even begin with this one? Right at the beginning, he goes hard. Starting with a lick that goes totally beyond what the guitars are playing, he uses slides to create the warm “bwoww” sound on the higher register to stand out from the low-string riffing of the guitars. He then goes back in key to play the rhythms along with guitar, then goes right back out with the same lick. It’s important to note that he goes back and forth between playing rhythms and leads, as without him emphasizing the low end, the band would sound empty. So he masterfully weaves between playing “rhythm bass” and “lead bass”, often within the same riff. Another great example is right after the intro, 29 seconds in, when the guitars transition to a riff that has low chugs followed by minor chords ringing. He hits the low notes along with the guitars, then when the guitars switch to the chords, he makes them the rhythm instrument and transitions to lead playing. Note how he slids in or out at the beginning/end of every lick to put that extra smooth sauce on there. And when the guitars would simply skip a string to reach a higher note, he just stays on the same string and slides into it, like Steve DiGiorgio in Death before him. He follows a similar pattern in pretty much every riff in the song with following the guitars when need be, then breaking out with his unique sound and creating a contrast. As mentioned many times here, fretless bass is about creating contrast. The push and pull between “inside” and “outside”, similar to dissonance (as per the article linked earlier), is what makes fretless so intriguing.

Of course, one can’t mention modern fretless bass playing in tech death without mentioning Jeroen Paul Thesseling (Pestilence) and his work in Obscura’s 2009 album Cosmogenesis. While Dominic Lapointe took the style to its extreme, Thesseling’s work on this album was what brought the instrument to the forefront in tech death and made it cool again, as for some period tech death had moved away from the delicious silky sound. “Anticosmic Overloard” single-handedly made it cool again, and is the main reason for why it’s so popular with tech death nowadays.

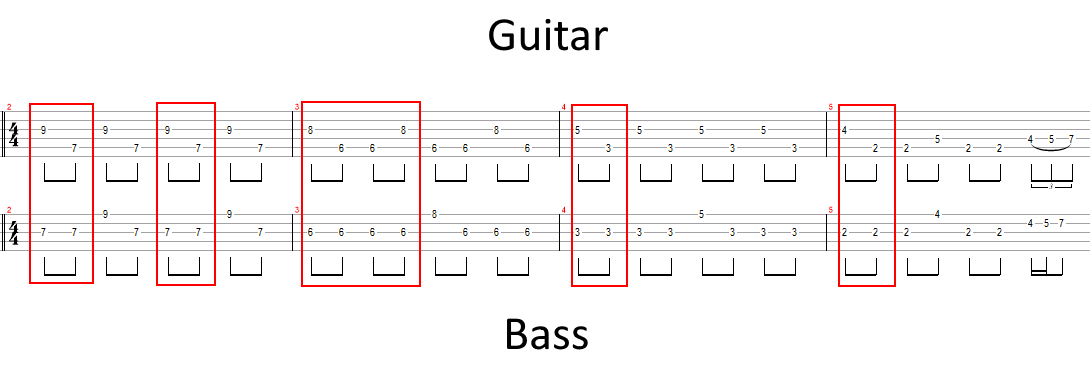

We see the same principles in this one as Lapointe’s work, going along with the guitars when need be then doing its own thing. However, one other thing that fretless bass often does is present here. While bassists often prefer playing note-by-note with guitars in rhythm sections, when playing very fast, that doesn’t always create an interesting sound, as bass doesn’t have the same amount of definition to it in the sonic spectrum. If you pay attention, during the main riff of the song, Thesseling plays mostly the same notes as guitar, but not in the same way. Let me demonstrate!

Now, don’t be intimidated! You don’t need to be able to read tabs to get this! Just note how the pattern played by the instruments differs in the places I’ve highlighted (among others). The 7s and 9s you see are octaves of each other, so they’re the same note, just lower. What the bass does is, sometimes it follows the guitar and plays a high-low pattern, other times it plays a low-low instead. Why? Because the higher you go on fretless bass, the more you’ll get the characteristic ringing sound of fretless, and by not doing that at ever opportunity, instead doing it every other time, Thesseling creates extra contrast that would otherwise be lost in the routine way of playing. This is the nuance of playing fretless, even when playing in key the unique, yes, “bwoww” sound of the instrument can be utilized sparingly to create extra, you guessed it, contrast!

Finally, as a closing example, I wanted to highlight some of Steve DiGiorgio’s later work. He was session bassist for the Canadian tech death band Quo Vadis, and his playing on their 2004 album Defiant Imagination encapsulates everything we’ve talked about so far. The song “Silence Calls The Storm” was my first introduction to fretless bass in metal and speaking to the band’s bassist Roxanne Constantin when they played live in Turkey was what made me pick up fretless bass as my primary form of bass, so let’s check it out!

In the intro riff, note how he plays mostly the rhythms, but at the end off each repeat, he adds a little lick that takes what would be a standard chugging riff and adds more character to it. Then we have the bass solo beginning at 57 seconds, with the smooth slide into position with a bass chord announcing the entrance of the fretless. The solo itself is a culmination of all the elements we talked about, with slightly off key notes, slides and the typical fretless sound. Then at 1 minute 12 seconds, we have the same trick as Obscura, with the rhythm guitars playing slow individual notes and the bass playing the same note, but keeps switching up the octave to hit the same note with the higher, more fretless-sounding timbre. The verse riff has the same trick as the intro, following the guitars then at the end of the riff diverging. The shenanigans continue until the end of the song, with a clean break near the end where the bass does its thing again. Overall, this song is a perfect example of all the techniques, and goes to show why Steve DiGiorgio is considered the innovator and master of fretless bass in metal by most.

Well, there you have it! Hopefully this primer of fretless bass in tech death gives you a sense of why and how the unique instrument is utilized by many prominent bands. The key thing to remember, which also applies to a lot of music, is that interesting music comes from establishing the rules and breaking them. Fretless bass wouldn’t be so cool if we all played fretless instruments with no 12-tone limitations to begin with. The contrast between normal notes and fretless notes, the interplay between following guitars and breaking free of them, that’s the essence of fretless playing.

Of course, there are many other examples of fretless playing, but I wanted to highlight the big, defining moments for the instrument, then add a pet favorite of mine. What are your favorite examples of the instrument? They’re not really tech death, but Intronaut also use fretless basses to great extent. While it’s less common to see it in other metal subgenres, fretless bass is still used by some bands, especially progressive ones. Also, shameless self-plug, as I also use fretless basses in my tech death solo project NYN!

I took over from Ahmed for this week, though he helped me write this, but next time he’ll be back in full force, so feel free to let us know in the comments what you’d like to hear about next time!

[photo: Joe Lester of Intronaut via Mark Valentino]