If you’ve followed Heavy Blog over the last few years, you know how much we love Bay Area “dark music” label The Flenser. They’ve cultivated an incredibly diverse roster that simultaneously features a collective consciousness among its artists, focused on producing genre-bending music outside stylistic conventions. So when I saw them announce To Sing of Damnation, I was instantly intrigued to see how that ethos would translate into their first full-length novel release.

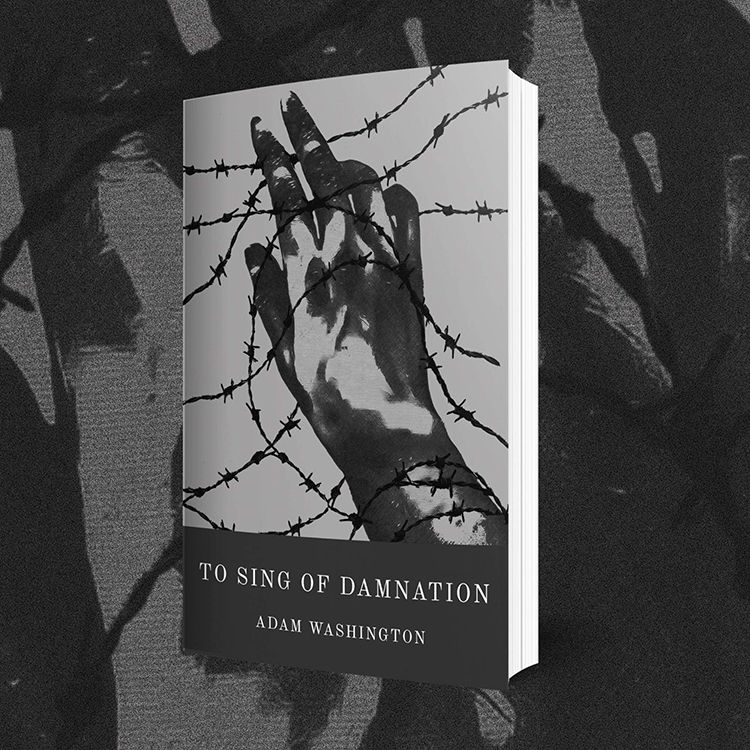

Virginia-based writer Adam Washington proves to be a more than qualified voice to shepherd in this new chapter of The Flenser’s output. To Sing of Damnation reads like a foundational text to an underground religion, like a blend of The Book of Job and The Stranger infused with darker, occult themes. Still grappling with complex grief over his father’s suicide, protagonist Jordan is attentions are quickly overtaken by Thorrauth, a daemon attempt to coerce him into a cryptic pilgrimage. Jordan’s mental and physical wellbeing begin to deteriorate as he attempts to rid himself of Thorrauth’s treachery, only to find himself dragged deeper into the mystery behind the daemon’s origins and intentions.

Washington writes with the deliberate, philosophical style of Albert Camus, colored in with pious fear and existential dread that defined ye olde English literature. Along the way, Washington touches on themes of God, suffering, and suicide, packaged under the overarching umbrella of evil’s source and purpose in our world. His prose is focused and precise, driving the story forward at an enticing pace without sacrificing any details or development along the way.

I wanted to spotlight this noteworthy moment in The Flenser’s history, and what better way to do that than talk to the people who know the label best? I’m thrilled to share conversations with Washington as well as Bryan Manning of The Flenser (and Bosse-de-Nage). They provide an in-depth look at the process behind releasing To Sing of Damnation, including the inspiration behind the novel itself as well as the connection that piqued The Flenser’s interest.

Adam Washington

Author, To Sing of Damnation

Obviously, a record label releasing a new novel is unique. The closest contemporary example that comes to mind for me is Sacred Bones, but they focus primarily on non-fiction and photography collections. How did you connect, and specifically, how did To Sing of Damnation come together?

We initially connected over The Misophorism Trilogy. I had self-published it at first and got copies printed, but it caught [The Flenser Founder and Owner] Jonathan Tuite’s attention and he was interested in selling a few copies in the store. A few copies eventually turned into many copies, and from that came To Sing of Damnation.

Besides the novel itself, my favorite part of To Sing of Damnation is the layout and art selection. How did you create the design? Was it a collaborative process?

That was pretty much all me. I selected all of the art myself, which mostly comes from old books from the 1800s about demons and the Book of Revelation. I commissioned the cover from Suzanne Yeremyan, who does a great deal of art for The Flenser. She’s an incredible artist.

Taking a general view, what inspired you to write To Sing of Damnation? What was your goal with this novel?

Great question. I’d say my goal was twofold; one: write the follow-up to The Misophorism Trilogy. Two: explore the themes of religion that I had always been interested in. Originally, it was just going to be Part 2 as a whole book, but Bryan Manning suggested that I add other parts to give it more context. Those other parts ended up being the core of the book. I wanted to explore long-held theological anxiety that had plagued me since I was a child as well. The idea of a fully omnipotent God, who is also fully benevolent, existing in a world where there is rampant suffering and unthinkable horrors committed by other people was something that had been on my mind for years. I was also familiar with and adored concepts such as misotheism; the ideology where one believes that God exists, but hates Him for the state of the world or for creating existence. Throughout the book, Jordan wrestles with the idea of fate, God, and death. It’s autobiographical in that sense.

The contradiction of an omnibenevolent and omnipotent God in a world such as this is called the Problem of Evil. The problem of “how can an omnibenevolent God create Hell?” is called the Problem of Hell. Both problems are personal interests and creative influences. Reading Thomas Aquinas’ rationalization of suffering as well as the Book of Lamentations in the Bible struck me. There is a great deal of religious work centered on the idea of suffering — and with suffering being such a big part of my work, I was drawn to them. These general concepts and philosophies formed the basis for To Sing of Damnation and Jordan’s struggle with God and fate.

The religious elements you created for To Sing of Damnation felt incredibly authentic, from the specific deities, prophets, and daemons to the language and dialogue. Personally, I found a lot of parallels with the Book of Job and “The Temptation of Christ.” What research went into outlining the central religion of the novel?

Thanks for saying that. I’ve always been interested in religion as I grew up in a Christian household. When I was a teenager I started to dive into it academically. Christian theology and biblical scholarship remained a large part of my creative inspiration as well as personal interest, which climaxed in To Sing of Damnation. Part of that interest resulted in me reading Paradise Lost years ago, which is where my grasp on the Middle English really started. John Milton and Shakespeare were major influences in that regard, as I read a ton of both to really get a handle on it.

So as far as specific research for the book, most of what I did was focused around the occult, since concepts like the Problem of Evil and the Problem of Hell were already familiar and themes in my work for a long time. But in researching Thorrauth, I came back to occult themes that I hadn’t worked with since 2015. It was part a refresher and part totally new, but it was wholly terrifying. Didn’t want to summon or demon or anything. So the sigils in the book are real sigils, but not for real demons — or even for fake demons. They were created using completely benign statements.

With the language, I had written an entire screenplay in Middle English at one point to get myself familiar with it, but for To Sing of Damnation, I tried to streamline it so that it could be understood by someone who doesn’t usually read it. A great deal of Middle English available to us today, such as Shakespeare and John Milton, is difficult to read because of the word order; the subject will be in the middle or end of the sentence, or it’ll have a complex structure in order to make it fit a number of syllables. So I got rid of all of that and made it similar to how we structure our own sentences.

As a New England native, I noticed underlying themes of Colonial piety and the fear of “The Wilderness,” especially as Jordan ventures to rural towns in the region. Why did you choose to set the novel in New England? Were these the general themes you were trying to convey?

To Sing of Damnation is part of The Misophorism Mythos; it exists in the same world that The Misophorism Trilogy does. In The Misophorism Mythos, New England is sort of a cursed location where everything bad happens, especially Havenroot, which represents reverence for death. At some point in my teenage years I remember someone I looked up to saying that New England was haunted. It stuck with me. The general idea of a rainy, gloomy area that seems haunted is something the misophorists would’ve been wholly drawn to. So with To Sing of Damnation, being the spiritual — and in some ways literal — successor to The Misophorism Trilogy, it naturally followed to set the book in that location. Jordan is a misophorist in his own right. It’s a similar reason why a big chunk of The Misophorism Trilogy takes place in the winter; everything is dead, something the misophorists would revel in.

While relatively short at ~150 pages, I felt like the narrative fit that length well, and there was never a wasted moment in the plot. How did you plan out the structure of the novel? Did you approach it with a general length in mind, or did the story itself dictate the page count you ended up with?

I planned it out in the same manner that I planned out screenplays for many years, which are usually around 90 to 120 pages. Books have thicker prose than screenplays, so it came out longer. When conceptualizing it, I was hoping it’d be around 200-300 pages, but as I was writing it, I realized I wouldn’t need that many. Some of the earliest writing advice I got was never to make a movie longer than it needed to be; write the story and keep it the length that it takes to tell the story. I carried that over to novel writing. I generally have a page length in mind but it almost always ends up shorter than the number.

What are you working on now, both in terms of your next novel and any other projects?

Currently, I’m working on the final book in the Misophorism Mythos, a book of aphorisms, and a personal project that I don’t plan to release, at least anytime soon. Creating art just for yourself is paramount. The character in that is my very first character and one that I’ve worked with from 2006~ to 2016 as his story became a full cinematic universe. Doing a reboot now is very fulfilling.

Rapidfire Round

First book/author that resonated with you?

Giles Corey by Dan Barrett [of Have a Nice Life and Black Wing]. I read it at 15 or so. It was the first time I saw a book that so vividly captured the emotions I had been feeling since I was a child and it was what got me comfortable with inserting more of myself into my writing.

Book/author that most influences your writing style?

Hard to pick one, but for To Sing of Damnation, it was The Stranger by Albert Camus, which is probably obvious to anyone who has read both books. More generally, Dan Barrett in his Giles Corey and Deathconsciousness zines.

Your all-time favorite book/author?

The Trouble with Being Born by E.M. Cioran. He’s also my favorite author. The Trouble With Being Born is pessimistic and antinatalistic philosophy in an aphoristic style. Surprisingly, though, he does not advocate for suicide. In fact, Cioran was the first author to fully remove the option of suicide from my head. I’ll always be thankful to him for that.

Best book/author you’ve read so far this year?

The Savage God: A Study of Suicide by A. Alvarez. It’s an incredibly thorough study of suicide that has a great deal of personal investment from Alvarez, and it really resonated with me as a result.

Bryan Manning

The Flenser | Vocalist & Lyricist, Bosse-de-Nage

Obviously, a record label releasing a new novel is unique. The closest contemporary example that comes to mind for me is Sacred Bones, but they focus primarily on non-fiction and photography collections. How did you connect, and specifically, how did To Sing of Damnation come together?

Jonathan (the founder and owner of The Flenser) and I have been talking about releasing books for a long time now. If I remember correctly, the idea first came up several years ago when I’d started working on a (regrettably still unfinished) novel. We’re both big readers and there’s already a fair amount of crossover with the music we release and literature. Have a Nice Life, Giles Corey, Street Sects, Drowse, and Bosse-de-Nage are probably the best examples of Flenser artists that have a literary bent to them.

I think we first met Adam through the Flenser Facebook group. He sent me an earlier draft of To Sing of Damnation last year and I gave him some general advice about the story. He’d also written a novel called The Misophorism Trilogy and at some point Jonathan offered to sell a few copies in our store. It did really well, so when Adam sent me a more advanced draft of To Sing of Damnation it was obvious that we should give it a proper release.

While To Sing of Damnation is The Flenser’s first full-length novel, you’ve released other literature before, including your own short story Blear and the book that accompanies the self-titled Giles Corey album. What is The Flenser’s publishing process, both in terms of connecting with authors and creating the final product? How does it differ from curating and distributing music?

We’re still working out the process in this department. It’s kind of similar to the beginning stages of the label itself with the releases being a bit more sparse as we make contacts and work out the best publishing practices. We haven’t built up a roster of writers yet or anything like that. So far it’s just Adam and myself, and whatever booklets we have that are included with records.

Books are a bit different than records, obviously, but there is some crossover. With the experience we have releasing records, it hasn’t been too difficult so far in terms of having a book produced. It was certainly helpful to have dealt with books to some degree in the past, like the aforementioned Giles Corey album and Have a Nice Life’s Deathconsciousness, among others.

Something I’ve always loved about The Flenser is your consistency with your “Dark Music” ethos. Regardless of the genre or medium, everything you put out truly feels like a “Flenser” release. Speaking more broadly, but also related to the books you’ve released, what goes into maintaining that consistent image? What do you look for when you consider adding an artist or author the The Flenser roster?

That’s tough to pin down. Generally I think we try to work with artists that have a certain kind of outlook more so than a specific sound. We both come from the world of heavy music, but there’s a whole wealth of artists that address “heavy” themes without necessarily playing metal or traditionally heavy music. We make it a point to seek out acts that don’t sound like the others on our roster, so there probably won’t ever be an easily quantifiable “Flenser sound.” It’ll always be evolving and a bit amorphous. Jonathan has a really great ear and just seems to know somehow when an artist is right for the label.

Do you plan on expanding more heavily into literature in the coming years, or will this be a case-by-case part of The Flenser’s output?

I do hope to release more literature in the future. As mentioned, we have more learning to do here, but we’d love to be more involved with the literary world.

While I have you, I have to ask about Bosse-de-Nage. You guys have always been a Heavy Blog favorite, and we particularly loved Further Still. What are you guys working on now?

Thanks very much! Unfortunately, BDN has been in a bit of a holding pattern since the pandemic started. We were almost four songs into a new album way back then, but at this point I’m not sure when we’ll get back to rehearsing regularly. It will happen, I just don’t know when precisely. I guess most people are probably in the same boat right now.

Bringing things full circle, did your affinity for lyricism prompt you to start writing fiction, or vice versa? And how have your two avenues for writing influenced your style over time?

I’ve always been interested in writing. I’ve wanted to write since I was a kid, but I never really had much confidence in my ability to do so. In the past, whenever I wrote something I would just throw it away afterwards. When we wrote the first BDN album I mostly used excerpts from books as the lyrics, hence the “Excerpt from…” song titles. But I did write lyrics for two of the songs and my bandmates seemed to like them, so when we wrote the second LP I wrote original lyrics for all the tracks.

There was a fair amount of positive attention given to the lyrics in reviews for the second and then the third BDN albums. This surprised me at the time, and was a real boost to my confidence. I thought, “I can actually do this,” so I became a bit more ambitious with my writing. I started working on a novel, which turned out to be a little too ambitious at that stage. I wrote a good number of words before I realized that I wasn’t quite ready to pull that off. Some knowledgeable friends helped me see that. I decided to scale back a little and work on a few short stories before returning to the novel, which I’ve been kind of working out more in my head in the meantime.

I think my forays into longer writing have shaped my lyrics into a more story-like form. This is especially evident to me on Further Still, and with the pieces I’ve been writing for whatever our next album will be.

Rapidfire Round

First book/author that resonated with you?

I think the first book that really resonated with me as an adult was Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov. I had a pretty pedestrian taste in books when I was younger, and that was the first work of literature that really caught my attention.

Book/author that most influences your writing style?

It’s difficult to choose only one book, but I’ll go with The Street of Crocodiles by Bruno Schulz.

Your all-time favorite book/author?

Another tough choice here, but I’ll say The Third Policeman by Flann O’Brien.

Best book/author you’ve read so far this year?

Ice by Anna Kavan. This was a really great novel about a nameless narrator searching for his former lover as the world turns to ice around them. Whenever he manages to catch up with her it’s always disappointing and anti-climactic. Very Kafkaesque. It also reminded me a lot of Kobo Abe’s work, who’s another author I love.