This is the second part of a series—for the first part, click here.

• • •

If there was one word to ultimately describe Miles Davis’s final handful of recordings, it would be “contentious”. While Davis was never too far away from controversy throughout his entire career, with a great number of his releases not finding proper reception until years after their release, this period of his life perhaps represented more of a disappointment by fans than any other. He’d been able to prove himself to be capable of serious experimentation with albums like Bitches Brew and On The Corner; one could only expect fans to be disappointed with the supposed lack of innovation found on The Man With The Horn.

While I don’t necessarily feel the same way about these recordings, it’s interesting to see Davis scholars like John Szwed (whose Miles biography So What has proven to be an invaluable resource in writing these articles) not be particularly enthused with what Miles put out at this time, with the general consensus changing little over time. The Man With The Horn, according to Szwed seemed to be “generally viewed as a weak recording. Those who had seen [Davis’s] new band were especially disappointed to hear a record by a group of musicians who seemed to have no relationship to what they had heard live.” Even Stereogum, in their own retrospective of Miles’s discography, placed a good portion of these final albums near the end, considering his final album Doo-Bop to be the worst album he ever recorded.

Opinions are opinions, though. Although I will never say that one’s personal thoughts on a piece of art are wrong, I do think that it’s always worth being open to music and trying things again. If we didn’t examine our own judgments from time to time, On The Corner would still be the wreck it was upon its release, rather than the ground-breaking album it’s viewed as today. Davis’s later career, granted, doesn’t have the same charm and/or spirit as previous eras of his discography show, but on looking back upon those eras, it becomes more and more obvious that Miles was constantly a trailblazer. As I said before in the first installment of this series, he was a musician that was constantly working forward. (After a while, he even refused to play bebop because, “I’d already done that. That shit makes me feel old.”) Couple this constant yearn for innovation with the fact that years of not playing trumpet (and significant drug use and medical problems) essentially erases any brass player’s embouchure, Man With The Horn and these other albums actually make sense—Miles is trying to do what he’s always done, but without all his tools (i.e. his style of playing) being fully available to him, or as fully available as they once were. I think that these next two albums, in a way, showcase his own problems on a personal level. While the previous article’s albums (Man With The Horn and Star People) seemed like a forced comeback, Miles seems to delve deeper in these next two, albeit in different ways—confronting his identity as a jazz legend in Decoy and as an African-American in You’re Under Arrest.

Decoy (1984, Columbia)

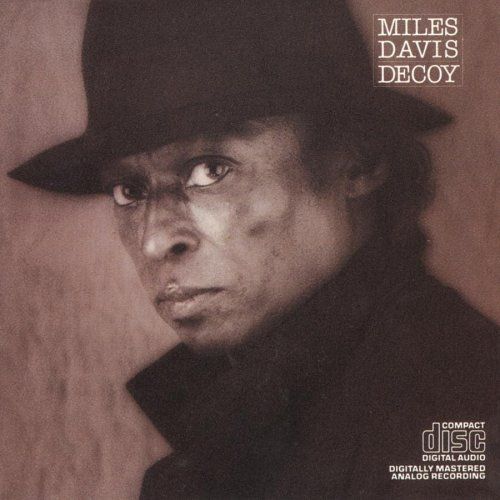

To best understand and/or describe Decoy, I suggest looking at the album cover below:

Immediately it’s noticeable that this is not the classic Miles Davis we once knew—the man who had his suits specially tailored so he could hunch over and play has grown older. He has noticeably aged here—his face has become a bit craggy. Most noticeably, though, he’s wearing what could be a PI’s outfit, as if he were about to star in a noir film. He speaks secrecy, and maybe the title speaks to that, in a way, that perhaps this isn’t the real Miles, but a purposefully-placed imposter.

Decoy, to put it simply, doesn’t really follow any trend previously followed by Davis. Miles doesn’t seem to pull and reinvent/progress beyond his past musical endeavors. While what we’re still listening to is undeniably post-retirement Miles—what with the heavy use of guitar and funk stylings, among other things—there’s something off about everything. By no means does this difference pertain to quality, however, as Decoy actually adds up to be a pretty damn good album.

Probably the biggest noticeable change between Star People and Decoy is in the arrangement and use of the personnel involved. Part of this has to do with Davis’s writing, as he seemed to step away for the most part from that duty and leave it up to keyboardist Robert Irving III and guitarist John Scofield to helm writing duties (though Davis does share a few credits with them, and one that’s solely his own, “Freaky Deaky”). Irving’s influence on this album makes the synth work much more obvious and hard-hitting than before, which I think was Miles’s intention—after all, even though he didn’t have as much to do compositionally with the album, he still produced it and arranged the music. At the end of the day, it’s still his work. This shift towards electronic music has been noted before, and has been a very gradual process since the beginning of the Electric Era.

Like I mentioned briefly before, the arranging on Decoy creates a much more full body of work. Early (i.e. pre-Electric Era) Davis was much more in the traditional mold of jazz—the drums and bass acted as the rhythm section and did little else besides that. In a way it was more like the trumpet and sax were the kings of each track. Bitches Brew broke this (as did the title track off of 1968’s Nefertiti), and allowed for each instrument to serve as more than just a small part of a bigger whole. Decoy brings this to a different level, as it’s not composed in the same “free” style those infamous Electric albums were—the bass and percussion still have a main duty to keep the vehicle of the track moving, but here they seem more able to go off on their own and become more expressive instruments with personalities as opposed to timepieces. The amount of electric guitar on this album in ratio to Miles’s trumpet playing is worth noting as well—John Scofield brings some serious soloing into this album.

However, it’s a little strange to see so much of a lineup change in only a year (Decoy being released in 1984, while Star People came out in 1983). While Bill Evans is listed as playing saxophone, it’s only for two tracks, with the other saxophone work being done by Branford Marsalis. Marcus Miller has been replaced with Darryl Jones (who, to his credit, does a great job), while Scofield handles Mike Stern’s guitar duties.

Maybe Miles is trying to suggest the idea of originality and perception by naming the album so—after all, we’re seeing change here. Perhaps its not huge change considering the albums that preceded this, but it’s nonetheless a shift. Maybe people at the time thought of Davis as a hollow reflection of his earlier self—his album covers used to be so colorful, and now they’ve become more muted than before. After building up steam and constantly innovating, maybe people wanted a follow-up to Bitches Brew, or something that would take jazz in a whole different direction, and Davis couldn’t/wouldn’t deliver on that. I can’t honestly say whether this is what he was thinking or not, but Decoy nonetheless represents another slight movement in the tectonics of Davis’s musical expression towards electronic music, and, to me, it’s done pretty well.

You’re Under Arrest (Columbia, 1985)

This album stands as a marker in many ways, a milestone for Davis’s career, though perhaps not a great one. You’re Under Arrest, for one of the first times in Miles’s career, puts political intrigue into music (if the title didn’t make that completely obvious), talking about, among other things, racism. He also covers two pop songs—another first—with recordings of Michael Jackson’s “Human Nature” and Cyndi Lauper’s “Time After Time”. More than anything, though, You’re Under Arrest is the final album he personally gave the green light to at Columbia Records, before moving to Warner Bros for Tutu and his remaining releases (with the exception of 1989’s Aura, which was recorded in 1984, back when Davis was still signed to Columbia).

So there’s quite a lot going on in this album, and it in many ways serves as a double-edged sword—Miles finally has his groove back, so to speak, but perhaps he put too much commentary into the music this time without giving enough focus to the music. Take the opening track “One Phone Call/Street Scenes”—it isn’t that it has uninteresting moments in it—Darryl Jones friggin’ rips it on bass, for one thing, and Scofield’s guitar playing is pretty great, despite it being in the background—but it’s also cluttered with sound effects and vocals trying to be a skit or sorts about an unfair, racially-discriminatory arrest of Davis by the police, which, for me, is where it fails. It’s not the themes that I’m against here, but rather the way it’s played out and performed. By this time, Miles’s voice has taken on such a raspy mumble that it’s tough at times to actually hear what’s going on, especially considering that there’s also an entire song being played below. (Apparently Sting, out of all people, makes an appearance on this track as well, saying the Miranda warning in French, but, like, looped backwards or something? I don’t know.) Outside of the context of this being a jazz album (and a Miles Davis album), I’ve found that many, many artists attempting to make a political and/or philosophical statement through their music can often forget about the quality and composition of the music being played, and as a result the track(s) with these ideologies in mind are often weak. It’s not that it can’t be done—it’s just extremely difficult to get the right balance down.

Covering popular songs isn’t unheard of in jazz—in fact, some of the greatest jazz tracks have been covers, such as Coltrane’s version of “My Favorite Things”. But what makes those covers so great is that the musicians are able to interpret the track in their own way, through the filter of their own musical style. Some people might find the idea of Miles covering pop songs on this album to be a little odd, and I thought of it as a potential goldmine, considering that Miles is both a great composer and performer and that the original covers of these songs are pretty great. However, it turned out to be a pretty big disappointment; there wasn’t really anything new about “Human Nature”, aside from Michael Jackson’s voice being replaced by Miles’s muted trumpet. (“Time After Time” suffers from the same problem, though I can’t say I’ve listened to Cyndi Lauper enough to really care.)

On Decoy, Miles seemed to be branching out into electronic music in a whole new way, finally taking on a style that didn’t have some previous basis in his discography, and with You’re Under Arrest you could make an argument for this, but this doesn’t mean it sounds good. It’s as if Miles had crossed some uncanny valley of electronic music during the time between releasing Decoy and recording You’re Under Arrest—nothing of a technical sort had changed during the recording of this album, yet the electronics here sound cheesy and saccharine, and—dare I say?—almost Kenny G-esque. (God…I feel gross even making that comparison.) It’s just way too smooth, especially for an album that’s supposed to be at least somewhat political and unnerving with its themes. I don’t necessarily think of elevator or easy-listening music as ripe with social commentary, but maybe I’m wrong. (To be fair, this album isn’t elevator music, but it gets dangerously close sometimes.)

However, I must stress that You’re Under Arrest isn’t without its interesting moments. The title track has this busy jazz fusion section of Eric Dolphy-esque proportions that remind anyone doubting Miles’s abilities in his later years that he’s still got some serious talent, and the final track “Jean Pierre/You’re Under Arrest/Then There Were None” finishes off with a really sweet synth part that sounds nearly taken out of Herbie Hancock’s Sextant album. But the best part of the entire album for me was the final moments of this last track, where Miles effectively puts politics into his music. It has this beautiful music-box melody playing above the roars of children playing, which is then completely completely overridden by what sounds like a nuclear bomb exploding and people screaming in terror, all with Miles playing over it—a creepy, bittersweet end.

Overall, I didn’t enjoy You’re Under Arrest as much as the albums preceding it, and that has mostly to do with Miles’s commentary bloating the music. Politics and music can (and often do) go together well, but the only time that it really worked here without either being confusing or overdone was at the end. It’s tough to remember that music can speak more about life than words ever can, and I think Miles only just realized this by the end of the album. This isn’t a great album, but it’s also not unlistenable or unrecommended, either—it’s just a bit of a step down from what Miles has proven himself capable of in these final years of his career.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cviww72mWUg